All about Rome under Mussolini

When I rented a house at Rome’s EUR district, the Square Colosseum (a building constructed during Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime) became part of my everyday view. On my way out and on my way back home, there it was, with its white walls, staring at me.

Between 1922 and 1943, period of the fascist regime in Italy, the Eternal City was subjected to a series of interventions as part of Mussolini’s propaganda. While speaking to Native Romans, I learned that my whole neighborhood had been designed by fascist architects, and that the Square Colosseum is just one out of many other fascist monuments still standing in the city.

The fascist dictator’s obsession with Rome might seem obvious given that the city is the country’s capital. Yet, the fact that Rome played a central role in Mussolini’s propaganda is more related to the power symbolism that he wanted to create by connecting his regime to the Roman Empire and himself to the figure of an emperor, which is why knowing all about Rome under Mussolini is indispensable to understand his mind and the development of Fascism in Italy.

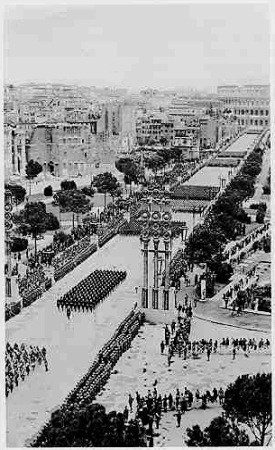

Rome, where fascists marched toward power

The fascist marching into Rome. Photo attributed to “Wide World Photos”. Source: “Benito Mussolini”, The Outlook, Vol. 132, No. 13, November 29, 1922, page 575 – WikiCommons

Although small fascist movements already existed in Italy during World War I, the official foundation of Fascism is considered to have taken place in 1919 in Milan after a meeting leaded by Benito Mussolini. The movement rapidly grew under his leadership, and only three years after its foundation, fascists enjoyed enough political influence to walk their way to power – literally.

In October 1922, Mussolini put his plan of a coup d’état in motion. Filled with confidence after a conversation with the US ambassador to Italy Richard Washburn Child, who declared the US had no objection to a fascist government and encouraged him to go ahead with his plan of ruling Italy, Mussolini organized on the 28th and 29th of that month a march on Rome.

Around 30,000 people marched across the city supporting the implementation of a fascist government. Meanwhile, militia squads known as “Blackshirts” were strategically placed all over Italy. Fearing a civil war – and also for sympathizing with fascist ideals – King Victor Emmanuel III officially made Mussolini the country’s youngest Prime Minister.

Mussolini, the wannabe emperor

The recreation of the Roman Empire through the development of a new Imperial Italy was one of Mussolini’s biggest ambitions. His plan consisted of annexing to Italy territories in France and the western Balkans claimed by irredentists, in addition to the acquisition of more colonies in Africa.

Alongside military actions in the aimed territories, Mussolini also invested massively in the construction of an ultranationalist imperial identity. For this, he worked at creating inside of the Italian people a feeling of grandeur and pride relatable to the Roman Empire. Other nations were also expected to see in the new Italy the same greatness of Ancient Rome. As the birthplace of the Roman civilization, the Eternal City became, then, the main target of the fascist propaganda.

Fascist architecture in Rome

In certain places, Rome’s vintage atmosphere is suddenly broken by geometric, usually white buildings constructed during Mussolini’s time. Known as Fascist architecture, the architectonic style that thrived in Italy during the early 20th century was a branch of Modernist architecture that carried elements of Rationalism and Stripped Classicism.

The Square Colosseum I mentioned before is a perfect example of this architectonic style. Originally named Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana (or Palazzo della Civiltà del Lavoro), the construction was designed in 1937 to host the Mostra della Civiltà during the 1942 World Fair (Esposizione Universale di Roma, EUR, in Italian). The several arches on the façade of the squared building pay tribute to the Flavian Amphitheater, which is why the construction became known as Square Colosseum.

In fact, the entire neighborhood where the palazzo is located was especially developed for the occasion of the 1942 World Fair, which was expected to be launched to celebrate the 20 years of Fascism in Italy. The neighborhood became known as EUR district. It brings together past, present and future, intentionally mixing Ancient Rome with Futurism in a clear representation of fascist utopia.

The fair never took place due to the outbreak of World War II, but the district remained as designed and became one of the busiest residential and business districts in Rome, just as Mussolini intended as he planned to turn the EUR into a modern city center alternative to the old one.

When I first stepped on the EUR district, I was impressed by the beautiful park, the big lake, the wide streets, and the huge corporate buildings. The Square Colosseum, however, caused in me a very strange feeling that I couldn’t describe. After discovering the history of the building and of the district itself, I understood how I felt and why: Fascist architecture didn’t just seek to impress; it also sought to intimidate.

Roads and railways built by Mussolini

If after all the investment in Rome people could not see Mussolini’s work easily, then it would have been in vain. After all, the modifications had more to do with the maintenance of the fascist regime than with the quality of life in the city. Thinking of that, Mussolini commissioned architects and engineers to design roads, avenues and railways that would connect important points in the city to each other, and Rome to other cities.

Roma Termini and Ostiense railway stations

One of Mussolini’s most famous projects was the reconstruction of the Roma Termini railway station. Differently from Paris, where trains departed from and arrived to different stations depending on where they were going and from where they were coming, Rome has had a central train station since the 19th century.

In 1937, Mussolini had the central station demolished and started rebuilding it in the fascist style. In 1943, when the fascist regime collapsed, the reconstruction was halted and remained unfinished until 1947, when a different group of architects worked on the completion of the Roma Termini project.

Despite the changes made to the design, the side structure of the station was kept as originally planned by fascist architecture and engineer Angiolo Mazzoni. Roma Termini is until today the busiest station in Rome.

In addition to the reconstruction of the Roma Termini railway station, Mussolini also promoted the construction of Roma Ostiense where once stood a rural railway station. The project was designed to welcome the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, who arrived in Rome by train on May 3, 1938.

A new road connecting the station to Porta San Paolo was also built and named Via Adolf Hitler. Mussolini and King Emmanuel III met the German leader at Roma Ostiense and drove him across the new street, where Hitler watched military parades dedicated to him.

After World War II, the street was renamed Viale delle Cave Ardeatine as a reminder of the Ardeatine massacre, which took place at the Ardeatine cave near the station in 1944 and had 335 innocent Italian civilians executed by German occupation troops.

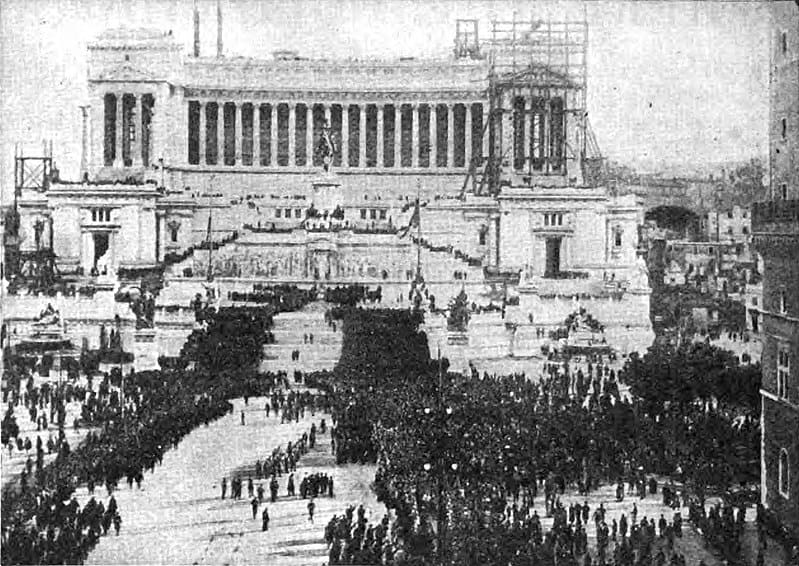

Via dei Fori Imperiali

Tourists know the Via dei Fori Imperiali very well. That’s because the street connects the monumental Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum, taking them only around 15 minutes to walk from one point to the other. What tourists usually don’t know is that before Mussolini, that street didn’t exist.

In 1924, the Italian dictator ordered the construction of the street as a route to nationalist parades inspired by the ancient Roman Triumph parades. While it was being built, the street was called Via dei Monti. In 1932, when it was inaugurated, it was renamed Via dell’Imperio. In that occasion, Mussolini performed the ribbon cutting ceremony and led on horseback a massive military parade. After World War II, the street was once again renamed to its current name.

The via facilitates the access to the Colosseum, Roman Forum and Palatine Hill, and many ancient ruins can be seen on each side of the street, where archeological excavations still take place. However, it all came with a high price. In order to establish the Via dei Fori Imperiali, Mussolini had to demolish medieval churches and part of ancient Imperial Forums. Thousands of residents were also displaced.

Along the years, the pollution caused by the traffic of vehicles in the street also started to hurt ancient monuments, including the Colosseum. Because of that, in 2013, Mayor Ignazio Marino closed the street for public traffic. Nowadays, the Metro C line is being constructed under the Via dei Fori Imperiali and only pedestrians, cyclists, taxis, municipal buses and chauffeured cars have access to the street.

Via della Conciliazione

Attempting to conciliate the relationship between the Vatican and the Fascist government, Mussolini initiated in 1936 the construction of the Via della Conciliazione, a wide street connecting St. Peter’s Square to the Castle Sant’Angelo.

Despite executing the plan, the idea of connecting the Vatican City to the center of Rome was not his. The first proposition of a boulevard from St. Peter’s Square to Rome was submitted by Leone Battista Alberti during the reign of Pope Nicholas V in the 18th century, followed by many other propositions.

At that time, the area where today lays the Via della Conciliazione was covered by residential, religious and historical buildings belonging to the Borgo district, the 14th historical district of Rome. When Italy was unified in the 19th century and the Borgo was incorporated into the Italian territory, the Roman Catholic Church protested and Popes refused to leave the Vatican City in order to avoid seeming conniving with the Italian government’s authority over Rome.

Before becoming Prime Minister, Mussolini openly criticized the Church. Once leader, the fascist dictator could no longer afford angering one of the most powerful institutions in the country. The construction of the boulevard, alongside a series of compensations and agreements, provided the expected results and the Catholic Church finally recognized unified Italy as a State.

Via della Conciliazione was only concluded in 1950, after the fall of Fascism and the death of Mussolini.

The creation of Cinecittà

The development of a fascist cinema was a priority for Mussolini. This became clear in 1937 when he founded a large film studio under the slogan “Il cinema è l’arma più forte” (“Cinema is the most powerful weapon”).

The Cinecittà Studio was expected to contribute to the fascist propaganda and boost the reputation of the Italian cinema. It was bombed during World War II; however, it was quickly reconstructed after the war. The entrance still has the rationalist style typical of Fascist architecture.

In the 1950’s, after the fall of Fascism, the studio gained a reputation as ‘Hollywood of the Tiber’ following the production of several acclaimed films. After a series of fires and near-bankruptcy, the studio was privatized. Lots of TV shows and TV series are currently shot there, such as Paolo Sorrentino’s series The New Pope, which premiered in Italy on January 10th, 2020.

The studio’s premises are open for visitation, where visitors have the opportunity to get immersed in the history of the Italian cinema. The Exhibition and Outdoor Set visit costs € 15. Children aged between 5 and 12 years old and people with disabilities pay € 7. The studio is open daily (except on Tuesdays) from 9:30 to 18:30.

Tickets to Cinecittà can be bought online or at the ticket office at Via Tuscolana 1055, 00173. The ticket office closes at 16:30.

In 2014, a movie-themed amusement park was inaugurated as part of Cinecittà, the Cinecittà World. Tickets for adults cost € 24 while tickets for children cost € 19. You can buy your tickets online at the park’s official website.

Cinecittà World is located at Via di Castel Romano and there are daily shuttle buses from Roma EUR Palasport metro station to the park and back for € 10. Check the shuttle bus schedule here.

“Those who do not remember the past…

… are condemned to repeat it.” It was this quote from George Santayana that kept me going while I was living at the EUR district. Having so many fascist landmarks around can make one feel suffocated sometimes. However, Santayana was right. Simply erasing all traces of fascist constructions from the map and pretending it never happened could backfire badly.

While history is always repeating itself, remembering the past can indeed teach us how to see and interpret red flags when they appear, so it is worth it to see and learn about what remained from the fascist regime in Rome. It’s also fascinating how Rome, accurately called the Eternal City, kept on shining and repurposed some of the things fascists left behind.

If you are in Rome with enough time to explore this part of the city’s history, do it. Do it and know it by heart.

Many tour agencies promote Fascist architecture tours and visits to the EUR district. You can also download the GPSmyCity app for a self-guided tour at the EUR district.

Planning a trip to Paris ? Get ready !

These are Amazon’s best-selling travel products that you may need for coming to Paris.

Bookstore

- The best travel book : Rick Steves – Paris 2023 – Learn more here

- Fodor’s Paris 2024 – Learn more here

Travel Gear

- Venture Pal Lightweight Backpack – Learn more here

- Samsonite Winfield 2 28″ Luggage – Learn more here

- Swig Savvy’s Stainless Steel Insulated Water Bottle – Learn more here

Check Amazon’s best-seller list for the most popular travel accessories. We sometimes read this list just to find out what new travel products people are buying.