Image by Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division from Wikimedia

10 Famous Historical African American Events in the US

African American history began with slavery, as white European settlers first brought Africans to the continent to serve as enslaved workers. Europeans arrived in what would become the present-day United States of America on August 9, 1526. With them, they brought families from Africa that they had captured and enslaved with intention of establishing themselves and future generations of Europeans off of the blood and sweat of these African families. During the American Revolution of 1776–1783, enslaved African Americans in the South escaped to British lines as they were promised freedom to fight with the British. Additionally, many free blacks in the North fought with the colonists for the rebellion and the Vermont Republic (a sovereign nation at the time) which became the first future state to abolish slavery.

Following the Revolution, numerous slaveholders in the Upper South freed their slaves and the importation of slaves became a felony in 1808. After the American Civil War began in 1861, tens of thousands of enslaved African Americans of all ages escaped to Union lines for freedom. Later on, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, formally freeing slaves in the Confederate States of America. After the American Civil War ended, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits slavery, was passed in 1865. In the mid-20th century, the civil rights movement occurred and racial segregation and discrimination were thus outlawed. The following are short descriptions of major events which have contributed to the shaping of African American history.

‘I Have a Dream,’ Speech -1963

On August 28, 1963, some 250,000 people (both Black and white) participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the largest demonstration in the history of the nation’s capital and the most significant display of the civil rights movement’s growing strength. After marching from the Washington Monument, the demonstrators gathered near the Lincoln Memorial, where a number of civil rights leaders addressed the crowd, calling for voting rights, equal employment opportunities for Black Americans and an end to racial segregation. The last leader to appear was the Baptist preacher Martin Luther King Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), who spoke eloquently of the struggle facing Black Americans and the need for continued action and nonviolent resistance.

“I have a dream,” King intoned, expressing his faith that one day white and Black people would stand together as equals, and there would be harmony between the races: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” King’s improvised sermon continued for nine minutes after the end of his prepared remarks, and his stirring words would be remembered as undoubtedly one of the greatest speeches in American history. At its conclusion, King quoted an “old Negro spiritual: ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’” King’s speech served as a defining moment for the civil rights movement, and he soon emerged as its most prominent figure.

Barack Obama Election as the 44th US President – 2008

Image by Erin A. Kirk-Cuomo from Wikimedia

On January 20, 2009, Barack Obama was inaugurated as the 44th president of the United States; he is the first African American to hold that office. The product of an interracial marriage—his father grew up in a small village in Kenya, his mother in Kansas—Obama grew up in Hawaii but discovered his civic calling in Chicago, where he worked for several years as a community organizer on the city’s largely Black South Side. After studying at Harvard Law School and practicing constitutional law in Chicago, he began his political career in 1996 in the Illinois State Senate and in 2004 announced his candidacy for a newly vacant seat in the U.S. Senate. He delivered a rousing keynote speech at that year’s Democratic National Convention, attracting national attention with his eloquent call for national unity and cooperation across party lines.

In February 2007, just months after he became only the third African American elected to the U.S. Senate since Reconstruction, Obama announced his candidacy for the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination. After withstanding a tight Democratic primary battle with Hillary Clinton, the New York senator and former first lady, Obama defeated Senator John McCain of Arizona in the general election that November. Obama’s appearances in both the primaries and the general election drew impressive crowds and his message of hope and change—embodied by the slogan “Yes We Can”—inspired thousands of new voters, many young and Black, to cast their vote for the first time in the historic election. He was reelected in 2012.

The Black Lives Matter Movement – 2013

Image by Ivan Radic from Wikimedia

The term “Black lives matter” was first used by organizer Alicia Garza in a July 2013 Facebook post in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman, a Florida man who shot and killed unarmed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin on February 26, 2012. Martin’s death set off nationwide protests like the Million Hoodie March. In 2013, Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi formed the Black Lives Matter Network with the mission to “eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes.” The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter first appeared on Twitter on July 13, 2013, and spread widely as high-profile cases involving the deaths of Black civilians provoked renewed outrage.

A series of deaths of Black Americans at the hands of police officers continued to spark outrage and protests, including Eric Garner in New York City, Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Tamir Rice in Cleveland Ohio and Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Maryland. The Black Lives Matter movement gained renewed attention on September 25, 2016, when San Francisco 49ers players Eric Reid, Eli Harold, and quarterback Colin Kaepernick kneeled during the national anthem before the game against the Seattle Seahawks to draw attention to recent acts of police brutality. Dozens of other players in the NFL and beyond followed suit.

The Million Man March – 1995

Million Man March Washington DC USA. Image by Ted Etyan from Wikimedia

In October 1995, hundreds of thousands of Black men gathered in Washington, D.C. for the Million Man March, one of the largest demonstrations of its kind in the capital’s history. Its organizer, Minister Louis Farrakhan, had called for “a million sober, disciplined, committed, dedicated, inspired Black men to meet in Washington on a day of atonement.” Farrakhan, who had asserted control over the Nation of Islam (commonly known as the Black Muslims) in the late 1970s and reasserted its original principles of Black separatism, may have been an incendiary figure, but the idea behind the Million Man March was one most Black and many white people could get behind.

The march was intended to bring about a kind of spiritual renewal among Black men and to instill in them a sense of solidarity and of personal responsibility to improve their own condition. It would also, organizers believed, disprove some of the stereotypical negative images of Black men that existed in American society. By that time, the U.S. government’s “war on drugs” had sent a disproportionate number of African Americans to prison and by 2000, more Black men were incarcerated than in college. Estimates of the number of participants in the Million Man March ranged from 400,000 to more than 1 million, and its success spurred the organization of a Million Woman March, which took place in 1997 in Philadelphia.

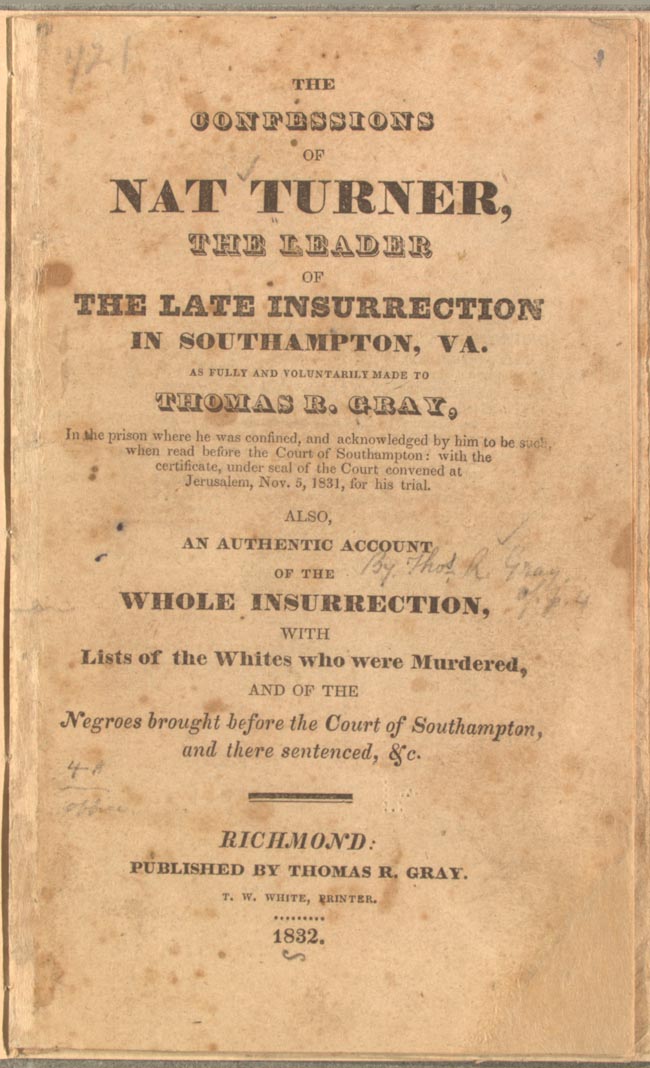

Nat Turner’s Revolt – August 1831

Image by Unknown from Wikimedia

In August 1831, Nat Turner struck fear into the hearts of white Southerners by leading the only effective slave rebellion in U.S. history. Born on a small plantation in Southampton County, Virginia, Turner inherited a passionate hatred of slavery from his African–born mother and came to see himself as anointed by God to lead his people out of bondage. In early 1831, Turner took a solar eclipse as a sign that the time for revolution was near, and on the night of August 21, he and a small band of followers killed his owners, the Travis family, and set off toward the town of Jerusalem, where they planned to capture an armory and gather more recruits. The group, which eventually numbered around 75 Black people, killed some 60 white people in two days before armed resistance from local white people and the arrival of state militia forces overwhelmed them just outside Jerusalem. Some 100 enslaved people, including innocent bystanders, lost their lives in the struggle. Turner escaped and spent six weeks on the run before he was captured, tried and hanged.

Abolition and the Underground Railroad – 1831

Image by Roseohioresident from Wikimedia

The Underground Railroad, a vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals — many whites but predominantly blacks who knew only of the local efforts to aid fugitives and not of the overall operation. Still, it effectively moved hundreds of slaves northward each year, according to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850. The early abolition movement in North America was fueled both by enslaved people’s efforts to liberate themselves and by groups of white settlers, such as the Quakers, who opposed slavery on religious or moral grounds. Though the lofty ideals of the Revolutionary era invigorated the movement, by the late 1780s it was in decline, as the growing southern cotton industry made slavery an ever more vital part of the national economy.

However, in the early 19th century a new brand of radical abolitionism emerged in the North, partly in reaction to Congress’ passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the tightening of codes in most southern states. One of its most eloquent voices was William Lloyd Garrison, a crusading journalist from Massachusetts, who founded the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator in 1831 and became known as the most radical of America’s antislavery activists. Antislavery northerners—many of them free Black people—had begun helping enslaved people escape from southern plantations to the North via a loose network of safe houses as early as the 1780s called the Underground Railroad.

Civil War and Emancipation – 1861

Emancipation Day – African American Civil War Memorial. Image by Ted Eytan from Wikimedia

In the spring of 1861, the bitter sectional conflicts that had been intensifying between North and South over the course of four decades erupted into civil war, with 11 southern states seceding from the Union and forming the Confederate States of America. Though President Abraham Lincoln’s antislavery views were well established and his election as the nation’s first Republican president had been the catalyst that pushed the first southern states to secede in late 1860, the Civil War at its outset was not a war to abolish slavery. Lincoln sought first and foremost to preserve the Union, and he knew that few people even in the North would have supported a war against slavery in 1861. By the summer of 1862, Lincoln issued a preliminary emancipation proclamation but on January 1, 1863, he made it official that enslaved people within any State, or designated part of a State in rebellion, “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

Pres. Lincoln justified his decision as a wartime measure and as such, he did not go so far as to free enslaved people in the Border States loyal to the Union, an omission that angered many abolitionists. By freeing some 3 million enslaved people in the rebel states, the Emancipation Proclamation deprived the Confederacy of the bulk of its labor forces and put international public opinion strongly on the Union side. Some 186,000 Black soldiers would join the Union Army by the time the war ended in 1865, and 38,000 lost their lives. On June 19, 1865, U.S. Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger issued General Order No. 3, which informed the people of Texas that all enslaved people were now free. This day has come to be known as Juneteenth, a combination of June and 19th. It is the oldest known celebration commemorating the end of slavery in the United States.

Founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) – 1909

Image by Terri Sewell from Wikimedia

In June 1905, a group led by the prominent Black educator W.E.B. Du Bois met at Niagara Falls, Canada, sparking a new political protest movement to demand civil rights for Black people in the old spirit of abolitionism. As America’s exploding urban population faced shortages of employment and housing, violent hostility towards Black people had increased around the country; lynching, though illegal, was a widespread practice. A wave of race riots particularly one in Springfield, Illinois in 1908 lent a sense of urgency to the Niagara Movement and its supporters, who in 1909 joined their agenda with that of a new permanent civil rights organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Among the NAACP’s stated goals were the abolition of all forced segregation, the enforcement of the 14th and 15th Amendments, equal education for Black and white students and complete enfranchisement of all Black men. First established in Chicago, the NAACP had expanded to more than 400 locations by 1921. One of its earliest programs was a crusade against lynching and other lawless acts. Those efforts—including a nationwide protest of D.W. Griffiths’ silent film Birth of a Nation (1915), which glorified white supremacy and the Ku Klux Klan—would continue into the 1920s, playing a crucial role in drastically reducing the number of lynchings carried out in the United States. Du Bois edited the NAACP’s official magazine, The Crisis, from 1910 to 1934, publishing many of the leading voices in African American literature and politics and helping fuel the spread of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s.

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott – December 1955

Rosa Parks Bus. Image by Unknown author from Wikimedia

On December 1, 1955, an African American woman named Rosa Parks was riding a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama when the driver told her to give up her seat to a white man. Parks refused and was arrested for violating the city’s racial segregation ordinances, which mandated that Black passengers sit in the back of public buses and give up their seats for white riders if the front seats were full. Parks, a 42-year-old seamstress, was also the secretary of the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP. As she later explained: “I had been pushed as far as I could stand to be pushed. I had decided that I would have to know once and for all what rights I had as a human being and a citizen.” Four days after Parks’ arrest, an activist organization called the Montgomery Improvement Association—led by a young pastor named Martin Luther King Jr.—spearheaded a boycott of the city’s municipal bus company.

African Americans made up some 70 percent of the bus company’s clients at the time and majority of Montgomery’s Black citizens supported the bus boycott, its impact was immediate. About 90 participants in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, including King, were indicted. Meanwhile, the boycott stretched on for more than a year, and the bus company struggled to avoid bankruptcy. On November 13, 1956, in Browder v. Gayle, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s decision declaring the bus company’s segregation seating policy unconstitutional under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. King, called off the boycott on December 20, and Rosa Parks—known as the “mother of the civil rights movement”—would be one of the first to ride the newly desegregated buses.

Voting Rights Act of 1965 – August 1965

Public Plaque on Voting Rights Act – Selma – Alabama – USA. Image by Adam Jones from Wikimedia

After the bloody intervention by state troopers of the Selma-to-Montgomery marchers’ in March 1965, President Lyndon Johnson addressed a joint session of Congress, calling for federal legislation to ensure the protection of the voting rights of African Americans. The result was the Voting Rights Act, which Congress passed in August 1965. The Voting Rights Act sought to overcome the legal barriers that still existed at the state and local levels preventing Black citizens from exercising the right to vote given to them by the 15th Amendment. It banned literacy tests as a requirement for voting and mandated federal oversight of voter registration in areas where tests had previously been used. Furthermore, it gave the U.S. attorney general the duty of challenging the use of poll taxes for state and local elections.

Along with the Civil Rights Act of the previous year, the Voting Rights Act was one of the most expansive pieces of civil rights legislation in American history, and it greatly reduced the disparity between Black and white voters in the U.S. In Mississippi alone, the percentage of eligible Black voters registered to vote increased from 5 percent in 1960 to nearly 60 percent in 1968. During the mid-1960s, 70 African Americans were serving as elected officials in the South, while by the turn of the century there were some 5,000. In the same time period, the number of Black people serving in Congress increased from six to about 40.

Planning a trip to Paris ? Get ready !

These are Amazon’s best-selling travel products that you may need for coming to Paris.

Bookstore

- The best travel book : Rick Steves – Paris 2023 – Learn more here

- Fodor’s Paris 2024 – Learn more here

Travel Gear

- Venture Pal Lightweight Backpack – Learn more here

- Samsonite Winfield 2 28″ Luggage – Learn more here

- Swig Savvy’s Stainless Steel Insulated Water Bottle – Learn more here

Check Amazon’s best-seller list for the most popular travel accessories. We sometimes read this list just to find out what new travel products people are buying.