The Causes of the French Revolution: Social, Economical, Political

There is something unique about the Revolution. Much more than a change of the political regime, it turned the French society upside-down in all its dimensions.

Since the beginning of the Revolution, the contemporaries tried to understand what happened, which actors and movements were to praise or to blame.

It is important to know that the causes of the Revolution are still a complex and much debated question today among historians.

The answers of the historians differ according to their political orientation but also depending on what they consider the most important drive for historical change: social, economic or political factors.

Another thing to keep in mind is that, for the Revolution or any historical event, nothing was written and nobody could have foreseen the outcome. It was not the accomplishment of a plan.

One example: in 1789 nobody wanted to get rid of the king. In 1793 the majority of the deputies sentenced him to the guillotine.

Different groups with different motives made a variety of actions and reactions and with hazard and luck, it turned into a reality that nobody expected.

Here, I will only briefly introduce you to the main explanations that have been given by contemporaries and historians over time.

I narrowed the question to what caused the events of the first year of the Revolution: 1789.

I think that what happened in the years that follow, and especially the Terror of 1793-1794, have more to do with what happened during the Revolution than with what happened before.

The Social Causes

The French society before 1789 is referred to as the Ancien Régime. The society was strongly divided by the status of the individuals and groups. There were 3 orders in the society.

On top, the nobility. The king could give to someone a title of nobility but this status was usually acquired by birth.

The nobles had all kind of privileges. The most important are that they would not pay taxes and they were given top-jobs in the army, the administration and the royal courtyard.

The nobles usually felt superior to the commoners and would let them know it.

The other privileged order was the clergy. The Catholic church was the official religion and occasionally persecuted religious minorities or deviant individuals.

There was the secular clergy in contact with the rest of the population and the regular clergy, the monks living in autonomy and quite secluded. Both were financed by a religious tax imposed on the commoners.

The clergy did not pay taxes while the church was the main landowner of the country. Each year, the church gave a financial gift to the state. The church chose the amount which was small compared to its richness.

The clergymen themselves were very divided between the high-clergy, whose members were coming from the nobility and the low-clergy, whose financial situation and everyday occupation made them feel close from the commoners.

The third order were the commoners, or the Third Estate (Tiers-Etat) as they were called at that time. They represented more than 90% of the population.

The majority of the commoners were peasants that had to pay the feudal rights to their lord like the right to use the ovens of the castles to bake their bread.

There were also many urban workers: craftsmen and workers in what we call today the services.

The resentment that many felt about the situation can be summarized in this anonymous caricature of 1789 where you can see a commoner supporting a noble and a clergyman. It is written “Let’s hope that this game will end soon”.

In the eighteenth century, the bourgeoisie had developed. Many urban families had a good education, were sometimes richer than the nobility but were denied access to the top-jobs. They felt humiliated to be considered inferiors to the nobles.

This organization of the society started to be criticized from the middle of the eighteenth century. The European philosophical movement called the Enlightenment started to challenge what has been unquestioned so far.

There was no apparent justification to the privileges given by birth to the nobles. The philosophers of the Enlightenment believed every man was born equal and had natural rights, what became men’s right. The equality with women was not mentioned.

An example of this critics can be found in a very successful play of 1786: Le Mariage de Figaro. Written by Pierre de Beaumarchais it featured a servant telling his noble master:

“Because you are a great lord, you believe that you are a great genius! You took the trouble to be born, no more. You remain an ordinary enough man!“

Some philosophers like Voltaire also undermined by their writings and political campaigns the moral and intellectual prestige of the Catholics church. Even if Atheism was very uncommon, some started to equate religion with superstition and intolerance.

The nobility and the monks were increasingly seen as parasites. As groups that had no social utility, no contribution to the richness of the country but cost a lot to the country.

The bourgeoisie was eager to access a political power corresponding to its economic power and the education level of their members.

Some parts of the working-class of the cities and the countryside were receptive to these critics. They mixed it with their own demands about the abolition of feudal rights and a right to be preserved from hunger.

This social factor created an intellectual atmosphere with many people turning angry against the privileges and a demand for rapid changes.

It explains why the deputies elected in the Assembly of 1789 went much further than what they were asked: to solve a financial problem.

In the summer 1789, the privileges of the church and the nobility were abolished and human rights were proclaimed. The monasteries were closed in 1790 and Catholicism was even forbidden in 1793, the church lost most of its economical power during the Revolution.

The bourgeoisie became dominant but with no significative improvement on the lives of the poorest.

The Economic Causes

The French monarchy was financially in trouble since the end of the reign of Louis XIV, the Sun-King, in 1715. The wars against many powerful European countries had left the country in a great debt that was even increased by the expenses of the crown.

The kings Louis XV and Louis XVI did not manage to stop the wars campaigns despite of their proclaimed will of peace.

In 1778, Louis XVI decided to support the American Revolution. This was a terrible blow to the old enemy of France, England, but also to the finances of the country.

The last years before the Revolution were marked by the attempts of Louis XVI to resolve this financial problem. The obvious solution was to make the nobility and the church to pay taxes but, as we will see, the king failed to obtain this from them.

Another very problematic issue was the bad harvests in the years that preceded the Revolution. In a rural country where the majority of the population has just barely enough to survive, any shortage of food could create famines.

Big cities like Paris, that relied on food supply from the countryside, were very vulnerable to these shortages or to the inflations of the prices.

Desperate people would riot against the people they consider responsible for the situation: the speculators, the local and national authorities. It could be easy for opportunistic politicians to direct the anger of the crowd against their opponents.

Many historians argued that this economic situation is the main reason to explain the start of the Revolution. They point out the correlation between increase in the prices of wheats and the start of revolts throughout French history.

Do most because are ready to risk their lives in rioting for high ideals about liberty and equality? Or, are they pushed into action because they are starving?

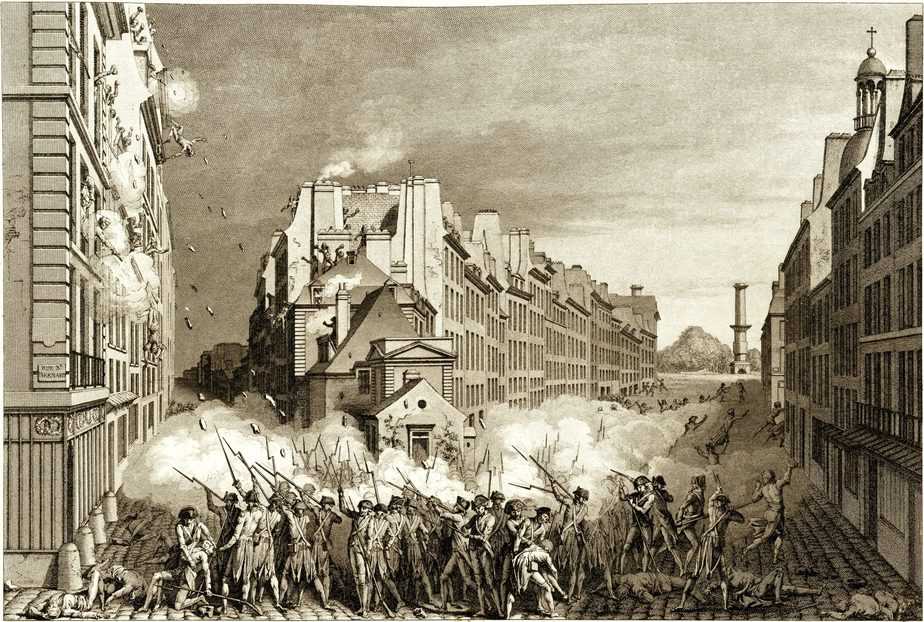

In April 1789, one month before the start of the Revolution, a big riot started in Paris. A manufacturer called Réveillon was rumored to wish a decrease of the wages. Starving Parisians riot while some claimed slogans like “Liberty!”.

Hundreds of workers were killed in the repression that followed. It is considered a sort of rehearsal of the riots of the Revolution.

The Political Causes

In theory, France lived in what was called an absolute monarchy. There was no Constitution or deputies to limit the power of the king. Louis XVI and the governments he chose were the only law-makers.

In practice, Louis XVI was expected to conform to Christian values and to respect the political traditions and privileges of the many separated territories that constituted the kingdom of France.

More importantly for him, Louis XVI had to deal with some rebellious local Parliaments. The parliamentarians were not elected deputies but judges belonging to the nobility. They were meant to assist and advise the king as his delegates and to register his bills, transforming them into laws.

These Parliaments turned into the only places where the policies of the government could be contested. The advices of the parliamentarians turned into reproaches and they refused to register the financial reforms decided by the king.

The parliamentarians presented themselves as the spokespersons of the nation and managed to obtain the support of many people. However, they were assemblies of nobles that defended their privileges and blocked the necessary financial reforms of Louis XVI.

The king was conscious of the necessity to make the privileges pay taxes in the interests of the country. He was not credited for his efforts in front of the public opinion. Instead he appeared as a weak king who could be easily defeated by an open opposition.

Some writers were paid by different groups of oppositions to write pamphlets against the ministers but also against the queen Marie-Antoinette. These personal attacks undermined the prestige and the popularity of the monarchy even if the king was still beloved by his people.

When Louis XVI acknowledged his impotence to reform the country by legal means, he turned into a risky solution. He summoned the General Estates (Etats-Généraux), a traditional assembly composed of deputies of the 3 orders that had not been summoned since 1694.

Legally, these deputies had only a representative role: they were meant to be the spokesperson of the localities where they had been elected.

Of course, there was a risk that these deputies claimed to represent the nation and give themselves the power of the deputies of the British Parliament or the American Congress.

Before the organization of the vote and the first meeting of this assembly planned in May 1789, the king took a radical initiative. He asked all the local assemblies electing the deputies to write the lists of their grievances in books called the Cahiers de Doléances.

All the French men received an unprecedented opportunity to express themselves directly to the king. This move from the king was very democratic and modern: it was well received as a sign that he cared about his people and valued their voices.

However, this was also risky. These people expressing their views expected to be listened and they had a very strong hope that the king will do the necessary changes to improve their conditions. These hopes turned later into frustration and anger when these changes did not come.

In June 1789 Louis XVI lost the control of the General Estates: the deputies declare themselves the National Assembly.

In July 1794, after the storming of the Bastille fortress, Louis XVI showed that he was at the mercy of the Parisians riots. His impotence resulted in the collapse of the royal administration and the election of local powers at every level: the Revolution had started.

***

As you can see, the explosive cocktail of the Revolution has different ingredients intertwined: a criticized social order, widespread ideas and hopes of change in a context of economic difficulties.

Some of these factors are long-term trends, some related to what happened shortly before the Revolution. There is also room for the actions and reactions of the groups and individuals involved.

It is likely that the Revolution could have been avoided if the duel between the king and the Parliaments had turned differently.

If the king had been firmer and more efficient or if the privileges had understood the necessity to give up some of their privileges, the political system might have evolved slowly and gradually like the British system.

If you want to get a more concrete understanding of the causes of the Revolution, I suggest a tour in Le Marais. Many of the buildings of this district were built in the XVIIIth century. You will feel the contrast between the luxurious private mansions of the nobles, the magnificent churches and the narrow streets and buildings were the commoners lived.

To know more about the Revolution itself you can visit the Conciergerie which holds a permanent exhibition about it.

Or you can ask for your private tour of the Revolution to see the places where history was made!

Planning a trip to Paris ? Get ready !

These are Amazon’s best-selling travel products that you may need for coming to Paris.

Bookstore

- The best travel book : Rick Steves – Paris 2023 – Learn more here

- Fodor’s Paris 2024 – Learn more here

Travel Gear

- Venture Pal Lightweight Backpack – Learn more here

- Samsonite Winfield 2 28″ Luggage – Learn more here

- Swig Savvy’s Stainless Steel Insulated Water Bottle – Learn more here

Check Amazon’s best-seller list for the most popular travel accessories. We sometimes read this list just to find out what new travel products people are buying.