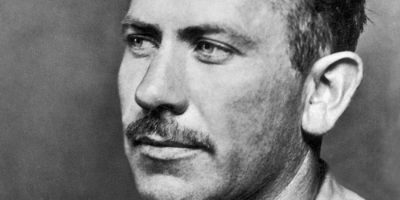

Computer-generated artistic illustration of racing driver Donald Campbell by Auge=mit – Wikimedia Commons

Top 10 Remarquable Facts about Donald Campbell

Donald Malcolm Campbell was a British speed record breaker who broke eight absolute world speed records on water and on land in the 1950s and 1960s. He remains the only person to set both world land and water speed records in the same year 1964.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, he volunteered for the Royal Air Force but was unable to serve because of a case of childhood rheumatic fever. He joined Briggs Motor Bodies Ltd in West Thurrock, where he became a maintenance engineer.

Following his father’s death on New Year’s Eve, 31 December 1948, and aided by Malcolm’s chief engineer, Leo Villa, the younger Campbell strove to set speed records first on the water and then on land. Campbell was a restless man and seemed driven to emulate, if not surpass his father’s achievements.

In this article, we look at the top 10 remarquable facts about Donald Campbell.

1. Campbell began his speed record attempts using his father’s old boat, Blue Bird K4

Campbell began his speed record attempts in the summer of 1949, using his father’s old boat, Blue Bird K4, which he renamed Bluebird K4. His initial attempts that summer was unsuccessful, although he did come close to raising his father’s existing record.

The team returned to Coniston Water, Lancashire in 1950 for further trials. While there, they heard that an American, Stanley Sayres, had raised the record from 141 to 160 mph, beyond K4’s capabilities without substantial modification.

2. Donald set seven world water speed records in K7 between 1955 and 1964

1962 Bluebird Campbell CN7 – Wikimedia Commons

The designation “K7” was derived from Lloyd’s unlimited rating registration. It was carried on a prominent white roundel on each sponson, underneath an infinity symbol. Bluebird K7 was the seventh boat registered at Lloyds in the “Unlimited” series.

Campbell set seven world water speed records in K7 between July 1955 and December 1964. The first of these marks were set at Ullswater on 23 July 1955, where he achieved a speed of 202.32 mph (325.60 km/h) but only after many months of trials and a major redesign of Bluebird’s forward sponson attachments points.

3. Campbell was awarded the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organizations, and public service outside the civil service.

Campbell was awarded the Order of the British Empire in January 1957 for his water speed record-breaking, and in particular, his record at Lake Mead in the United States which earned him and Britain very positive acclaim.

4. Donald developed an ambition to build a car to break the land speed record

A photo of “Blue Bird” by Agence de presse Mondial Photo-Presse – Wikimedia Commons

It was after the Lake Mead water speed record success in 1955 that the seeds of Campbell’s ambition to hold the land speed record as well were planted. The following year, serious planning was underway to build a car to break the land speed record, which then stood at 634 km/h set by John Cobb in 1947. The Norris brothers designed Bluebird-Proteus CN7 with 500 mph in mind.

Following low-speed tests conducted at the Goodwood motor racing circuit in Sussex, in July, the CN7 was taken to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, United States, the scene of his father’s last land speed record triumph, some 25 years earlier in September 1935. The trials initially went well, and various adjustments were made to the car. On the sixth run in CN7, Campbell lost control at over 360 mph and crashed. It was the car’s tremendous structural integrity that saved his life.

5. Campbell was the only person to set both land and water speed records in the same year

In 1964, Campbell now planned to go after the water speed record one more time with Bluebird K7. He wanted to do what he had aimed for so many years ago, during the initial planning stages of CN7, break both records in the same year.

After more delays, he finally achieved his seventh water speed record at Lake Dumbleyung near Perth, Western Australia, on the last day of 1964, at a speed of 276.33 mph. He had become the first, and so far only, person to set both land and water speed records in the same year.

6. Donald decided to try once more for a water speed record in 1966

To increase publicity for his rocket car venture, in the spring of 1966, Campbell decided to try once more for a water speed record. This time the target was 300 mph. Bluebird K7 was fitted with a lighter and more powerful Bristol Orpheus engine, taken from a Folland Gnat jet aircraft, which developed 4,500 pounds-force of thrust.

By the middle of December, some high-speed runs were made, in excess of 250 mph but still well below Campbell’s existing record. Problems with Bluebird’s fuel system meant that the engine could not reach full speed, and so would not develop maximum power.

7. Campbell’s last words, during a 31-second transmission, on his final run were, via radio intercom

On 4 January 1967, weather conditions were finally suitable for an attempt. Campbell commenced the first run of his last record attempt at just after 8:45 am. Bluebird moved slowly out towards the middle of the lake, where she paused briefly as Campbell lined her up.

Mr. Whoppit, Campbell’s teddy bear mascot, was found among the floating debris and the pilot’s helmet was recovered. Royal Navy divers made efforts to find and recover the body but, although the wreck of K7 was found, they called off the search, after two weeks, without locating his body. Campbell’s body was finally located in 2001.

Campbell’s words on his first run were, via radio intercom. The cause of the crash has been variously attributed to several possible causes.

8. Donald Campbell was posthumously awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Brave Conduct

In the public bar of the Sun Hotel, Bluebird Bitter (named after Donald Campbell’s boat) was available by Peter Trimming – Wikimedia Commons

The Queen’s Commendation for Brave Conduct, formerly the King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct, acknowledged brave acts by both civilians and members of the armed services in both war and peace, for gallantry not in the presence of an enemy. Established by King George VI in 1939, the award was discontinued in 1994 on the institution of the Queen’s Commendation for Bravery.

On 28 January 1967, Campbell was posthumously awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Brave Conduct for courage and determination in attacking the world water speed record.

9. Campbell and his father had set 11-speed records on water and 10 on land

The story of Campbell’s last attempt at the water speed record on Coniston Water was told in the BBC television film Across the Lake in 1988, with Anthony Hopkins as Campbell. Nine years earlier, Robert Hardy had played Campbell’s father, Sir Malcolm Campbell, in the BBC2 Playhouse television drama “Speed King”; both were written by Roger Milner and produced by Innes Lloyd.

In 2003, the BBC showed a documentary reconstruction of Campbell’s fateful water-speed record attempt in an episode of Days That Shook the World. It featured a mixture of modern reconstruction and original film footage. All of the original color clips were taken from a film capturing the event, Campbell at Coniston by John Lomax, a local amateur filmmaker from Wallasey, England. Lomax’s film won awards worldwide in the late 1960s for recording the final weeks of Campbell’s life.

10. Campbell’s daughter gifted the recovered wreckage of Bluebird K7 to the Ruskin Museum

Ruskin Museum Donald Campbell Bluebird K7 by Paul Hermans – Wikimedia Commons

On 7 December 2006, Gina Campbell, formally gifted the recovered wreckage of Bluebird K7 to the Ruskin Museum in Coniston on behalf of the Campbell Family Heritage Trust.

In agreement with the trust and the museum, Bill Smith is to organize the restoration of the boat, which is now underway. Now the property of the Ruskin Museum, the intention is to rebuild K7 back to running order circa 4 January 1967.

In August 2018, initial restoration work on Bluebird was completed. She was transported to Loch Fad where she was refloated on 4 August 2018. For safety reasons, there are no plans to attempt to reach any higher speeds.

Planning a trip to Paris ? Get ready !

These are Amazon’s best-selling travel products that you may need for coming to Paris.

Bookstore

- The best travel book : Rick Steves – Paris 2023 – Learn more here

- Fodor’s Paris 2024 – Learn more here

Travel Gear

- Venture Pal Lightweight Backpack – Learn more here

- Samsonite Winfield 2 28″ Luggage – Learn more here

- Swig Savvy’s Stainless Steel Insulated Water Bottle – Learn more here

Check Amazon’s best-seller list for the most popular travel accessories. We sometimes read this list just to find out what new travel products people are buying.